February 17 2026, 08:15

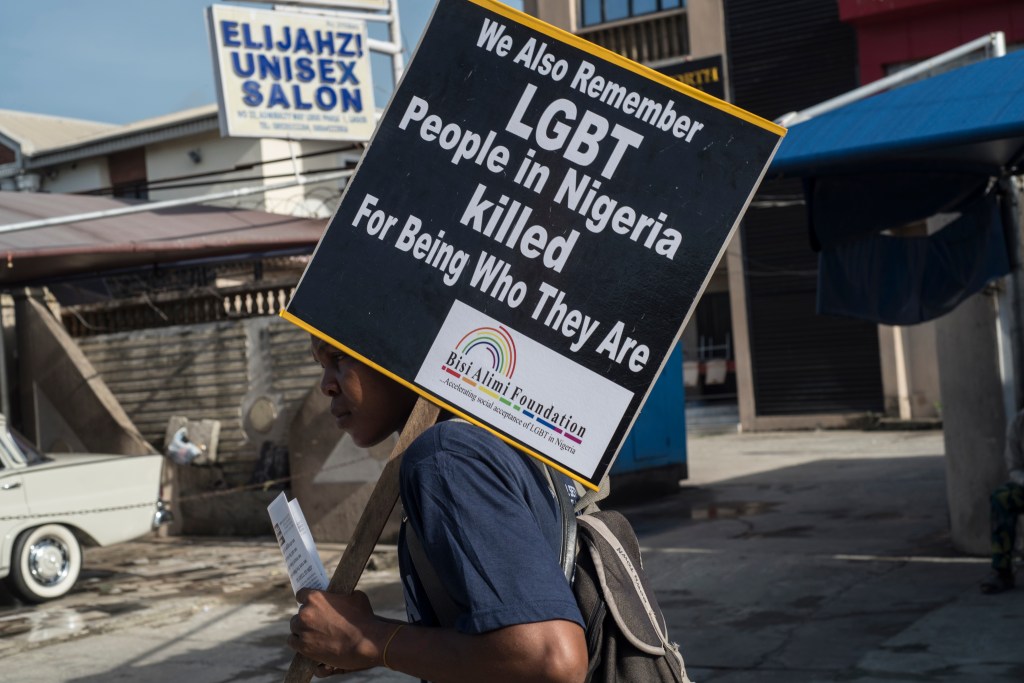

February 17 2026, 08:15 The UK’s asylum system’s designation of Nigeria as a “safe country” poses real risk to queer Nigerians facing persecution, reporter Daniel Anthony outlines for PinkNews.

Under UK asylum policy, Nigeria is treated as a country that is generally stable rather than affected by civil war, active conflict, or a failing government. It is listed as a safe country of origin for men, meaning UK authorities presume that, in general, there is no serious or widespread risk of persecution or indiscriminate violence.

However, for queer Nigerians, this perception of safety is misleading and dangerous.

In Nigeria, safety can disappear with a whisper, a hint of effeminacy, a phone search, a neighbour’s suspicion, or the arrival of police who know that Nigeria’s homophobic laws will protect them and justify whatever horrific fate they are about to impose on you.

Nigeria prohibits same-sex relationships under federal law. The Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (SSMPA), enacted in 2014, criminalises same-sex relationships and in several northern states, Sharia-based penal codes impose severe penalties, including the death penalty.

In August of last year, two secondary school students were beaten to death by their classmates after being accused of homosexuality. In a separate incident a month prior, videos surfaced online showing two university students being attacked by a mob over similar allegations. Violence of this nature has become disturbingly normalized in Nigerian schools, often supported — and at times applauded — by school authorities, with little to no accountability for those responsible.

Weeks later, in September, a young gay man named Hillary was thrown from a three-story building to his death because of his sexual orientation. Earlier this year, during New Year celebrations in northern Nigeria, two underage girls were stoned to death after being accused of lesbianism, without evidence, trial, or mercy.

Perhaps the most widely reported case is the murder of Abuja Area Mama, a well-known TikTok creator and LGBTQI+ figure. In August 2024, her stabbed and mutilated body was found by the roadside in Nigeria’s capital. No suspects have been identified, and the case remains unsolved — a grim reminder of how easily fatal violence against queer people fades into silence.

Often, violence against queer people in Nigeria is not condemned but celebrated. Videos of beatings, abuse and public humiliation circulate widely online, filmed by bystanders and shared for entertainment. Comment sections fill with applause, mockery, and calls for harsher punishment, signalling that violence against LGBTQI+ people is not only tolerated but socially rewarded. In this environment, harm is learned early, repeated often, and carried out with impunity — collapsing any meaningful distinction between mob violence and state violence.

Rights groups say this is not exceptional. In 2023, more than 1,000 violations based on real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity were recorded, and in 2024, civil society monitors documented 556 violations affecting over 850 people — a snapshot they believed to represent only a fraction of actual unreported incidents.

One common form of abuse is “KITO”, where queer men are lured online, taken to private locations, beaten, filmed, and blackmailed — with videos sent to families and threats of exposure or death if ransoms are not paid.

Survivors report that this cycle of abuse, which accounts for about 70 per cent of the mistreatment of queer individuals in Nigeria, has driven many victims to despair and suicide.

One gay man from Nigeria, now living in the UK after being granted asylum, described how a “KITO” attack permanently altered the course of his life, an experience that left him deeply traumatised and suicidal.

“That incident ruined my life,” he told me. “I tried taking my own life, but it didn’t work. I was depressed and I became a shadow of myself.”

He said the psychological damage outlasted the physical violence. Returning to daily life in Nigeria after his exposure meant living under constant ostracization, repeated attacks, and public scrutiny.

“There was no safety after that,” he said. “You’re just waiting for the next thing to happen.”

With the help of a friend, he eventually fled and sought asylum in the UK.

The contrast, he said, was stark.

“I spent 30 years of my life in Nigeria. But in just over a year here, I’ve had more peace than I ever had back there,” he said. “I would rather jump in front of a speeding bus — than relive that experience again. That kind of life, I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

What haunts him most, he added, is not only what he survived, but the people he left behind.

“There are still men like me back there, dealing with this every day,” he said. “That’s what breaks my heart.”

This is the reality many queer Nigerians are fleeing — and the context UK asylum policy increasingly fails to account for.

Under the UK government’s proposed asylum reforms, safety is being treated as a fixed for a nation, assessed from a distance and applied broadly. As the asylum system tightens, claims are judged less on lived risk and more on whether a country is deemed generally “safe”.

For LGBTQI+ Nigerians, whose danger is constant and systemic, this approach is especially dangerous.

In practice, this logic misreads how persecution operates. The violence enabled by Nigeria’s Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act — police extortion, arbitrary arrests, mob attacks — is routinely treated as incidental rather than structural. When asylum seekers raise these experiences in the UK system, they are often dismissed as isolated incidents or deemed insufficiently severe, leaving LGBTQI+ applicants with an almost impossible evidentiary burden.

This is where the UK’s latest reforms, which would make refugee status contingent on a country of origin never becoming safe, become dangerous and further reinforce misconceptions. By relying more heavily on country-of-origin designations, the system shifts away from group-specific risk and toward blanket assessments that assume danger must be universal to be credible.

But queer persecution rarely works that way.

LGBTQI+ people are targeted precisely because they are minorities. Their persecution is localised, informal, and socially enforced — carried out by families, vigilantes, or corrupt officials rather than through formal state channels. These realities rarely leave paper trails and do not fit neatly into asylum frameworks that privilege documentation and national stability over lived risk.

How does one document a lynching that no authority investigated?

How does one prove the constant threat of exposure in a society, where queerness itself is treated as criminal intent?

Charities supporting LGBTQI+ asylum seekers warn that this gap routinely leads to wrongful refusals, even as the Home Office acknowledges that LGBTQI+ people from countries like Nigeria face persecution. Rainbow Migration has assisted Nigerians whose claims were rejected by the UK government on credibility grounds, overlooking the surveillance, blackmail, and violence faced by queer individuals in the country.

This is both a moral and legal failure. According to the 1951 Refugee Convention, individuals persecuted for their sexual orientation or gender identity are entitled to protection, regardless of their country’s overall safety. International law only requires that the risk of persecution is real and that the state fails to provide protection.

There is also a history that remains largely unacknowledged.

Nigeria’s criminalisation of same-sex relationships is rooted in British colonial rule, which imposed sodomy laws later absorbed into postcolonial legal systems and currently being reinforced by political and religious leaders. Yet when queer Nigerians seek asylum, Britain positions itself as a neutral evaluator of safety — without reckoning with its role in shaping the danger they are fleeing.

If the UK is genuinely committed to its human rights obligations, it must reject the misleading simplicity of “safe country” narratives. The safety of minorities cannot be determined by national averages. Asylum systems should be evaluated not on how effectively they exclude people, but on whether they adequately protect those who are most in need.

For queer Nigerians, asylum is not a policy abstraction. It is a vital lifeline.

The post When ‘safe country’ is a death sentence: Why the UK’s asylum reforms endanger queer Nigerians appeared first on PinkNews | Latest lesbian, gay, bi and trans news | LGBTQ+ news.