One unseasonably warm spring day in 2020, my dad and I ventured from New Jersey to a storage unit in Orange County, New York, to unearth the remnants of my great uncle Nicky’s life. Since his death in 2018, these belongings had lain dormant, preserving the enigma of his vibrant and contradictory existence. From sculptures by local artists to heartfelt letters, old plane tickets, and my great-grandparents’ immigration papers—each item was a mosaic piece of the man I deeply wish I had known better.

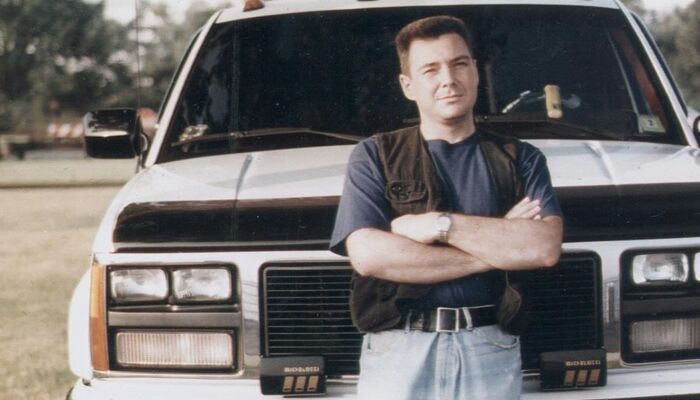

He was an enigma who led a life of bold colors – red for his boots, green for his eyes – and daring choices. Relatives often described him as “eccentric,” a striking, extravagant figure who left a mark on every room he entered. “You knew Nicky was there when he entered a room,” my mother recently told me, delighted to have the opportunity to talk about him so long after his death. Uncle Danny used to say, “Everything was over the top for him.”

Related

The lessons my Uncle Lloyd taught me belong to Black History Month

But in one area, Uncle Lloyd was unsuccessful. That was a good thing in hindsight.

Nicholas De Cresce was more than just my great uncle; he was a fixture in my family, albeit one I never knew well enough. His life had everything: travel, art, music from the British Invasion era, and high-class food. Nicky was an emblematic part of the Greenwich Village scene in the 1970s and 1980s. His collection of ‘60s and ‘70s British Invasion and glam rock records was enough to stock a whole record store, even today. Most importantly, he had an eye for the finer things: fashion, art, museums, makeup, language, and everything.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

He also shared my passion for history. As I grew into my teens, he started to send unexpected texts about historical facts he’d learned during one of his frequent trips to the New York Public Library. His support for my musical aspirations—which had just begun at his death—was steadfast, culminating in a gift that spoke volumes: a vinyl copy of the Doors’ 1967 self-titled album.

That was the last Christmas we had him around. His death from lung cancer just before his 59th birthday in 2018 cut short what could have been a full-fledged friendship, complete with abundant common interests. Through posthumous conversations – via his friends’ memories and the letters he left – I’ve done everything I can to tap into that unshared knowledge and begin to understand Nicky as both a relative and as a misunderstood man who navigated his identity in a world that was changing around him.

Nicholas De Cresce (née Passaretti) was born in 1959 in Jersey City, the youngest son of Italian immigrants Giuseppe and Gilda De Cresce. Nicky’s upbringing, rooted in old-fashioned, rural values, was in many ways incompatible with his growing personality. Nicky was isolated by his older parents and much older siblings during his adolescence.

Despite the tumultuous, atomized environment of the 1960s, he realized he was gay in seventh grade. He left for Manhattan, just across the Hudson, where he found a community that celebrated him.

Nicky never forgot where he came from, however. He cherished his Italian heritage and constantly lauded his parents’ work ethic amidst the difficulty of immigrating to an unfamiliar country. He is buried alongside his mother at Holy Cross Cemetery in North Arlington, New Jersey, with a headstone reading “Mother and Son Reunion.”

In 1977, Nicky crossed the Hudson River to Chelsea as a Fashion Institute of Technology student. Though his childhood home and his newfound community were only five miles apart, he might as well have switched universes. His flair for fashion and his gay identity could flourish in his adopted environment, and his peers met him with radical understanding and acceptance. His friendship with Virginia “Ginny” Hildebrandt, a fellow student, grew amid Studio 54’s lively nights, where Ginny ran the VIP section. Nicky’s days in New York were a whirlwind of style, music, and confident self-expression, integral to cultural shifts. He could visit quirky art galleries and museums during the day and dance to disco all night long in his three-inch red boots, and no one bothered him.

“I had all these special guests, like Grace Jones, Peter Allen, and the Rolling Stones, and Nicky was always with me….He was rock and roll – like David Bowie. He loved all that stuff,” Ginny fondly remembered the days at the Studio 54 VIP lounge. “Every block, there was something going on. There was a lot of culture around, art on the streets, everything.”

Despite a bustling social life, Nicky was unable to find a stable job. He dabbled in various jobs, including stints with airlines – a nod to his love of travel – but by the mid-90s, he faced career stagnation after several years in Houston and returned to the East Coast. As he aged, his life became a contradiction of high society soirées and personal economic struggles. He had the mind of a worldly, sophisticated socialite, yet he could never get a stable career off the ground.

Amidst his financial and health troubles, Nicky lived with others. This included Ginny in Chelsea and my own immediate family during our London stay.

Despite his inability to integrate into the professional realm, my mother was quick to clarify that Nicky was “not a moocher.” He always helped out around the house when he stayed over, brought gifts for his loved ones (like my Doors record or my sister’s jewelry box), and made an effort to connect with those around him, like when he took my dad to museums in the city in his youth and helped me with my college application process.

He applied his work ethic to other spaces, which I did not know until after his death. His dedication to social causes, for example, was evident in his volunteer work with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and a 30-year tenure at the Suicide Prevention Hotline, demonstrating his commitment to helping others. He also volunteered with the Sandy Hook Foundation at the Jersey Shore. He contributed to the preservation of National Historical Landmarks along the coast.

The piece of my uncle that people remember the most, however, was his personality. He was always making some kind of a scene, in the kind of way that no one can forget looking back. My mom recalled, almost immediately, the family dinner after my Christening in Jersey City in 2000. Nicky was the first to arrive at the Italian venue from the church. Despite the fact that my mom had pre-planned the courses, Nicky told the bar to replace the pre-paid house wine with bottles of far more expensive wine, running up the bar tab by a casual few thousand dollars when no one was looking. When my mom asked him about it, his only answer was, “I didn’t want you and Christopher [my father] to be embarrassed by cheap wine on the table.”

My mom – who is not related to Nicky by blood but occupied a significant role in his life – has an even better story. She took him in for his medically urgent liver transplant in 2005, and though his body was on the brink of failure, he walked in unassisted holding a Gucci shave kit “in case [he] wanted a shave” during his hospital stay. When the nurse arrived later to shave him for the upcoming surgery that same day, he promptly pulled his leg from under the blanket to reveal that it was already completely bare. “You don’t have to shave me, honey,” my mom recalled him saying to the nurse. “I’ve been getting electrolysis since the ‘80s. And girl, at that time, it was painful.”

As a cisgender, heterosexual young musician with a passion for hard rock, my life and identity might seem worlds apart from Uncle Nicky’s experiences in the vibrant gay culture of Greenwich Village in his day. I always felt, though, that we had commonalities. We could have really connected about music, history, or Italian culture had he been around longer. There are so many common interests that underlie the differences on the surface, and my efforts to learn about my uncle have only confirmed that.

I’ve come to understand the importance of documenting gay lives like Nicky’s. It is, on the one hand, a preservation of family memory, which his gravestone suggests is meaningful to both of us.

It’s even more than that, though. My exploration of my uncle’s history has taught me that being different from your environment, for whatever reason, is a strength and not a weakness. His persona – interests, sexuality, quirks, everything – made his life challenging at times, though it also gave him the distinctive aura he was known for. Everyone who ever met him remembered him, and here I am, writing about him almost six years after his death. His identity and personality left a mark on those who knew him, which is powerful in itself.

Sifting through Nicky’s remnants has been more than an exercise in nostalgia. It explores a life that refused to conform. Though he never found conventional success, he left a family full of people who love and miss him dearly. They are still telling stories about him years later, which is just what I suspect he always wanted.

Each anecdote and artifact implied stories of defiance and identity that pushed against temporal convention. What I’ve learned from Nicky isn’t just to embrace authenticity but to recognize how profoundly one person’s unfiltered self can echo through others’ lives.

In the stories I’ve uncovered from my uncle’s life, both told and implied, I’ve pieced together a story of unfettered self-expression, which always shone despite the earthly struggles of age, environment, failing health, finances, and everything else. Though he and I are very different people, that is the universal lesson I can learn from him, even all these years later.

The impact we leave on those around us is the only thing that remains when we’re gone. That’s what makes Nicky’s life, ultimately, a success.