This is an excerpt from LOVE: The Heroic Stories of Marriage Equality, a new book by Frankie Frankeny that celebrates the history of the LGBTQ+ community’s fight for marriage equality from the 1950s to today. This triumphant journey is presented in compelling stories of the pioneering couples, along with winning photographs. The book is available from Rizzoli New York.

“Is your dance card full?” Edie asked the dark-haired woman whose back was to her. Hearing her voice, but without turning around, Thea answered, “Now it is.” Their flirtation, and a love of dancing together, had started two years earlier, in 1963, when they met at a mutual friend’s apartment. The flirtation continued that afternoon in the Hamptons, an artsy enclave outside New York City that had been attracting the LGBTQ+ community since the 1950s.

Edie Windsor was determined to see Thea that weekend, making a series of telephone calls before finally finding a spare room in the very house where Thea would be staying. Those who knew Edie would say this was no surprise, as Edie tended to get what Edie wanted.

Related

Gay uncle writes book to explain PR to his niece

“Have you seen social media? It’s already trending in three countries! Get Denyse on the line. And someone wake up Tom!”

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

The youngest child of a Russian Jewish immigrant family in Philadelphia, Edie had her first lesbian experience at Temple University. Under societal pressure and family expectations, Edie married Saul Wiener, convincing him to change his last name to Windsor out of concerns about antisemitism. Six months later, Edie asked for a divorce after admitting she was a lesbian. With her degree from Temple, Edie moved from Philadelphia to New York’s Greenwich Village. While working a secretarial job, Edie earned a master’s degree in mathematics from New York University, leading to her pioneering career in software development at IBM, in an era where the industry was almost exclusively male.

Thea Spyer, the daughter of Dutch Jews who fled the Netherlands in the 1930s, was known as a heartbreaker in the New York and Hamptons lesbian communities. A clinical psychologist and gifted violinist, Thea had switched her major at Sarah Lawrence College from music to psychology after being passed up for first violin, a sign of her headstrong ways and refusal to settle for second best. After her expulsion from Sarah Lawrence for being a lesbian, Thea continued her studies at City University of New York, earning a master’s degree in clinical psychology, and eventually a PhD in clinical psychology from Adelphi University.

Despite their attraction and connection, Thea wasn’t interested in a committed relationship and frequently cancelled on Edie. Edie’s desire for a relationship and Thea’s aversion to being tied down created complications for the couple, as Thea expressed in a letter she once left for Edie: “I wish I could really be something for you, something substantial, but I can’t, not now, probably never.”

Frustrated by Thea’s continued inability to choose her, and her alone, Edie ended things and refused to answer Thea’s calls or visits. Weeks later, during an unexpected 2:00 a.m. telephone call, Thea promised that there would be nobody else but Edie. “I love you,” followed a year later, in the summer of 1966.

That same summer, Thea asked questions about Edie’s marriage to Saul, surreptitiously probing Edie’s feelings on marriage itself. When asked if she would wear a ring, Edie said she couldn’t explain an engagement ring to her colleagues, but she would wear something else, perhaps a pin, something that wouldn’t prompt colleagues to ask awkward questions.

When they arrived at their Hamptons rental one summer weekend, Edie jumped out of the car to go into the house, but Thea asked her to wait. Turning back, Edie found Thea kneeling with one knee on the ground and a small jewelry box in hand. As Thea proposed marriage with a pin of twenty-two diamonds placed in a circle, Edie enthusiastically responded, “Yes!” This circle of diamonds affirmed their relationship as firmly as any traditional engagement ring.

The couple filled their life with friends, travel, budding activism, and the ever-constant love of dancing together. During the summer of 1976, their dancing was occasionally interrupted when Thea’s right knee would give out. In the months that followed, Thea experienced occasional falls, stiffness, numbness, and other symptoms. Thea continued to brush off Edie’s suggestions to see a doctor as unnecessary.

The unusual symptoms continued to plague Thea, culminating in a diagnosis of progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1979. Thea’s physical abilities degenerated quickly, and she encouraged Edie to leave her to avoid being a caregiver. Edie reminded Thea that they were engaged, that they were in this together no matter what. Despite her physical decline, Thea’s mind remained sharp, and she continued to see her patients while the couple adapted their two homes and routines to support her declining physical abilities. They also continued to dance, refusing to let anything—not even a wheelchair—keep them from the joy they had found together on a dance floor since their first meeting in 1963.

When New York’s mayor issued an order allowing same-sex couples to register as domestic partners beginning March 1, 1993, Edie demanded that Thea cancel her therapy appointments so that they could go to city hall. As usual, what Edie wanted, Edie got, and they were the eightieth couple to register that day. Three years later, President Bill Clinton signed the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) into law, which defined marriage as between one man and one woman, which prevented the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages in any way. Meanwhile, Edie and Thea’s very long engagement continued, marked by a love and commitment that never diminished.

As Thea’s MS progressed, Thea’s heart became weakened to such an extent that her physician recommended heart valve replacement surgery. However, she and Edie decided against it—despite the doctor’s prognosis that Thea would die within a year without the surgery—because Thea and Edie had previously agreed that there would be no hospital stays. The next morning, Thea asked Edie if she still wanted to get married. Edie said yes, and they began planning a marriage in Canada, thanks to the province of Ontario legalizing same-sex marriage in 2003. With the assistance of the Civil Marriage Trail Project, an organization that facilitated wedding travel to Toronto for same-sex couples, they made the trip to Canada with a small group of friends.

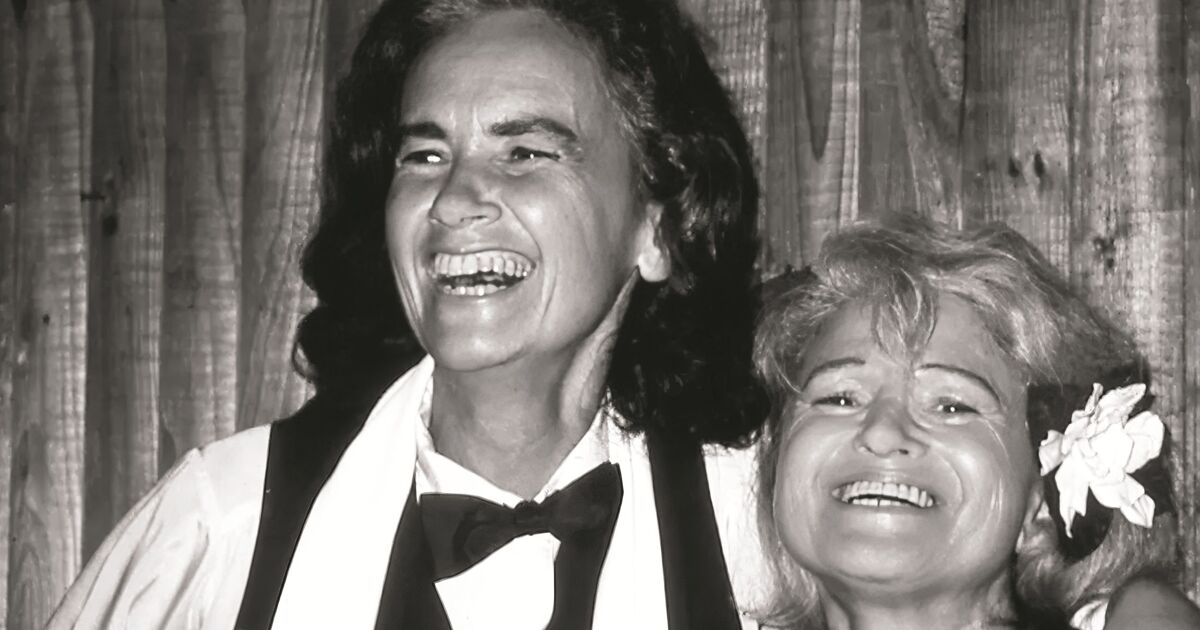

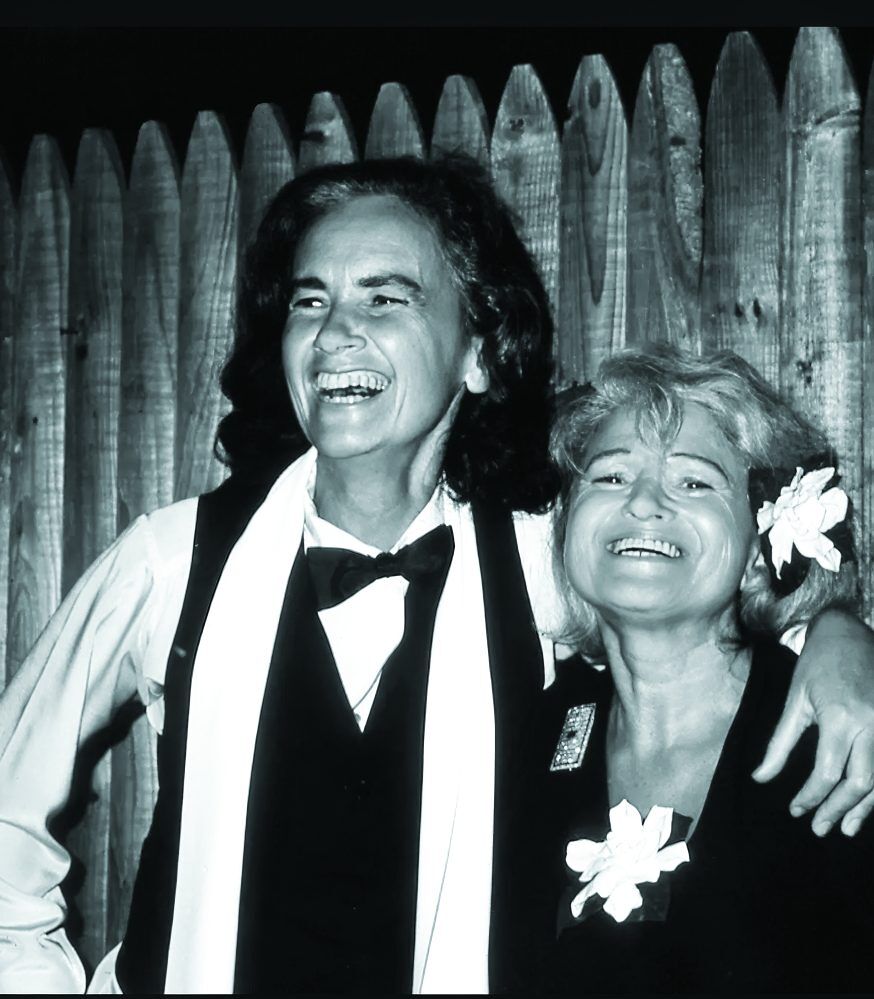

After forty-two years together, Edie and Thea exchanged vows on May 22, 2007, in a hotel conference room at Toronto Pearson International Airport. In a ceremony officiated by Justice Harvey Brownstone, the first openly gay judge in Canada, they acknowledged their decades as a couple with their vows: “With this ring, I thee wed… from this moment forward, as in days past.” The commitment that once could not be publicly recognized with a ring finally came full circle.

Edie and Thea’s dance continued until Thea’s death on February 9, 2009. A month later, Edie suffered a heart attack and was diagnosed with stress cardiomyopathy, also known as broken heart syndrome. Heart issues took a back seat to outrage when the IRS and the State of New York billed Edie a total of $638,000 in inheritance tax on Thea’s estate. Due to DOMA’s restrictions, the IRS and the State of New York could disregard their lawful marriage and deny Edie the spousal estate tax exemption enjoyed by opposite-sex couples.

Refusing to accept this injustice, Edie enlisted Roberta Kaplan, an attorney who agreed to take on the case pro bono. In a strange twist of fate, Roberta had briefly been a patient of Thea’s in the early 1990s. In 2010, they filed a lawsuit in US District Court to demand a refund of the taxes levied on Thea’s estate. The US Justice Department decided not to defend DOMA, prompting the House of Representatives to hire an outside attorney in the Justice Department’s place. In a win for Edie, the US District Court judge declared Section 3 of DOMA unconstitutional, a ruling later affirmed by the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. The US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) accepted the government’s appeal of Edie’s win and heard arguments in the case on March 27, 2013.

As Edie explained: “In the midst of my grief at the loss of the love of my life, I had to spend countless hours defending my relationship to the federal government.” Those countless hours came to an end on June 26, 2013, when SCOTUS’s decision in United States v. Windsor struck down DOMA and ended the seventeen-year federal ban on same-sex marriage. Edie’s last name became synonymous with a major advance in LGBTQ+ equality, boosting her prominence as a New York LGBTQ+ activist to the national stage.

Willing to fight for what she wanted, Edie found success in her career, and she found success in love. That love and her willingness to fight injustice brought down a discriminatory law and gave hope to millions of Americans. Touching on her love and loss during a June 26, 2013, press conference at Stonewall Inn, Edie said, “If I had to survive Thea, what a glorious way to do it.”

Edie found love again and married Judith Kasen on September 26, 2016. On September 12, 2017, Edie died suddenly following a medical procedure. During the memorial service at New York’s Temple Emanu-El, Hillary Clinton thanked Edie for “being a beacon of hope. For proving that love is more powerful than hate.”

Subscribe to the LGBTQ Nation newsletter and be the first to know about the latest headlines shaping LGBTQ+ communities worldwide.