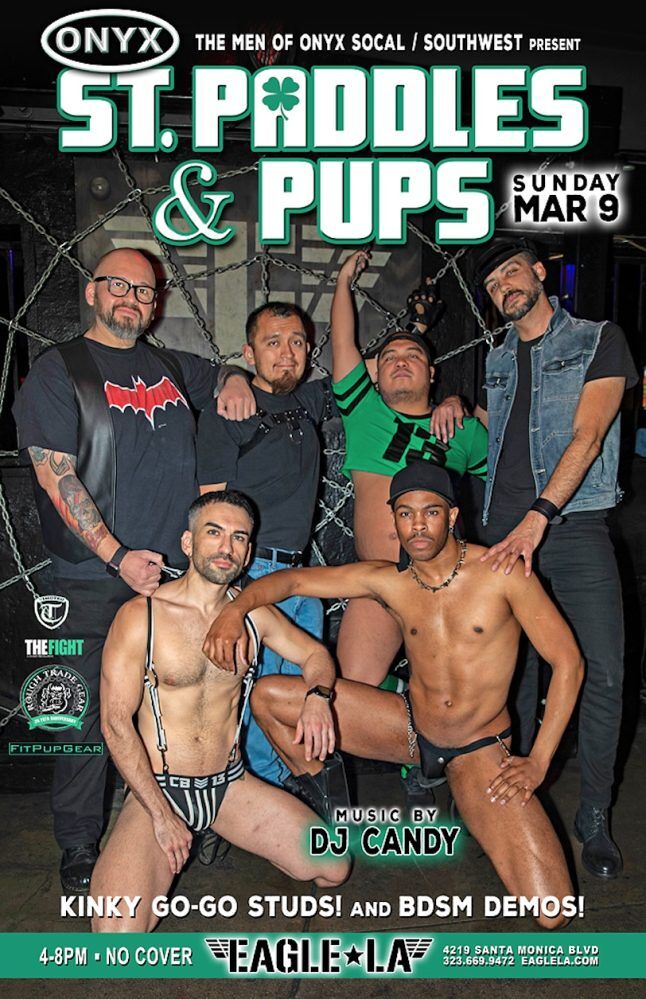

Six new pledges adorned in black leather boots, green puppy hoods, and camo gear await the start of their first event as full fledged members of ONYX Southwest, a group for queer leathermen of color. As two arrange a spanking booth — an array of various paddles for bar patrons to choose from — five other members put on jockstraps and harnesses, ready to go-go dance.

Scout Onyx walks around the Los Angeles Eagle leather bar, breaking up small talk among ONYX’s members to ensure they have raffle tickets and Jello shots to sell in time for the patrons’ 4 p.m. arrival. The more ready they are, the more money they will raise for the Trans Wellness Center.

Related

“The Aunties” elevates the lifechanging role of intergenerational Black queer friendship

“You deserve mentorship, you deserve the love of the older generation, and you have to be worthy of your deservings,” said one of the filmmakers.

This March 9 “St. Paddles and Pups” event is just one of 20 community fundraisers that ONYX Southwest will hold this year for local charities. Since its inception in 2015, the group has raised over $64,000 for various charities.

Never Miss a Beat

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay ahead of the latest LGBTQ+ political news and insights.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

One might not expect a bunch of QPOC leather kinksters to be the sort of group that would fundraise for community service charities, but to Peeker Onyx — who has served as the organization’s president since the start of this year — the overlap makes sense.

“I’ve experienced homelessness, I’ve experienced addiction, I’ve experienced losing jobs and being poor and not knowing where I was going to eat,” Peeker tells LGBTQ Nation. “I was eating 7-Eleven burritos and White Castle sliders for a month… So it’s like, these same things affect the community: being hungry, not knowing how they’re going to get their medications, being laid off, and they just feel hopeless.”

Systemic racism has prevented many people of color from accumulating generational wealth, he adds, forcing some people (like himself) to depend on the kinds of organizations that ONYX now fundraises for.

“I never thought I’d be participating in something like this, that’s kind of deviant and at the same time helpful to the community.”

ONYX Southwest President Peeker Onyx

Peeker — which is an alias, similar to the ones taken on by all Onyx members — first learned of Onyx while drinking and hanging out at Cell Block, a longtime kink and leather bar in Chicago’s Boystown gay district.

“I’ve always been leather adjacent,” he says. “I’ve always been curious, but I never felt I could participate.”

He would regularly ask a drinking buddy about the leather events he attended. When Peeker finally attended one himself, he met other Onyx members who encouraged him to join.

“I was really hesitant,” he says. “I felt like the time commitment was too much probably, or I felt like I wasn’t as advanced [in kink] as some of them. But I went to a few events. The guys were amazing. It was a lot of camaraderie. Everybody was very sweet. I realized I didn’t have to have leather gear. I didn’t have to be advanced.”

He later moved to Los Angeles, and when the COVID shutdown happened, he felt very lonely without a committed group for social support. But he eventually attended a local ONYX event and immediately “fell in love” with the group.

He then went through the six-month new member pledgeship process — which involves introducing one’s self to other members, attending two fundraiser events, and getting a “big brother” sponsor. After a year and a half as a full member, he found himself serving as his chapter’s president; something he said he never thought he’d do.

“I do volunteer service work in another nonprofit for sobriety,” he says. “Like, I’m sober six years. I do a lot of drug and recovery outreach, but I never thought I’d be participating in something like this, that’s kind of deviant and at the same time helpful to the community.”

Collectively, the 42-member group — whose cohort covers Southern California, Utah, Las Vegas, Nevada, Colorado, and Arizona — has raised thousands of dollars for groups like the HIV/AIDS support organization Being Alive, the queer homeless charity Cityx1 Youth Group, the Okaeri support group for LGBTQ+ Japanese-Americans, and a community health and wellness organization for Latine people called the Wall Las Memorias Project.

As 175 patrons circulated through the Eagle, one Onyx member squirted Jello shots from hypodermic syringes directly into men’s mouths — there’s Margarita, Very Berry, and Mango Twist flavors: $5 for one or $10 for three. Another shirtless Onyx member walked around with a roll of raffle tickets, offering a single ticket for $1 and a “crotch to boot” span for $10. The $10 option always gets jokes about measuring things from people’s crotches — some buyers ask if they can measure the span using their tallest friend, so they can get the most amount of tickets for just 10 bucks.

Around 6:30 p.m., an ONYX member with a bullhorn tells everyone to prepare their tickets for the drawing. The prizes include Timoteo underwear, Cellblock 13 jockstraps, fetish items from Fit Pup Gear and Rough Trade Gear, two leather shops owned by people of color. But most importantly, the men of ONYX Southwest reveal that their event raised around $500 for the Trans Wellness Center.

At the next fundraiser several weeks later, the Onyx men present a big novelty check to a representative from the Trans Wellness Center as well as two other beneficiaries, giving them much smaller actual checks in envelopes later on backstage.

ONYX Southwest is just one of the 11 chapters under the national ONYX organization, which is dedicated to offering community, education, and empowerment to men of color interested in leather, sadomasochism, and fetish play. Mufasa Ali founded the national organization in Chicago in 1995, at a time when most leather organizations had predominantly white leadership.

Mufasa (as he is known by ONYX’s members, who often refer to each other by first names only) said that he wanted to create a “leather Green Book” — a reference to the pre-Civil Rights travel guide for Black motorists — so that leathermen of color would know where to find brotherhood when attending leather conferences, play parties, pageants, dances, and fundraisers. The internet helped the group thrive by making its members and events much easier to find. Before then, people just had to enter a leather bar and ask around to hopefully find an ONYX member in attendance.

“I need to be around people that subscribe to the values and practices of the leather community, but also have similar experiences of exclusion and otherness.”

ONYX Southwest member, Ali Mushtaq

“Whether it’s the work of Tom of Finland or portraits of past [International Mister Leather (IML)] titleholders, the image of the leather community has long been awash with white, cisgender, traditionally masculine faces,” wrote Black leatherman Mikelle Street.

While that’s changing, people of color still face challenges in the leather community: being stereotyped, fetishized, or mistaken for others of the same ethnicity or skin color; being under-represented in leather and kink marketing and pornography; or being treated as unimportant or outvoted by predominantly white memberships in kink organizations.

Because the gay leather aesthetic originated in part from white motorcycle gangs and World War II Nazi regalia, white supremacist imagery and echoes of racism persist — some recent instances of which have been called out by ONYX members.

“I don’t feel like a brother in the community,” ONYX Southwest member Ali Mushtaq wrote. “[I feel] like a statistical anomaly. “I need to be around people that subscribe to the values and practices of the leather community, but also have similar experiences of exclusion and otherness.”

White kinksters might not know that flogging bruises look different on non-white skin. They also may not realize that the history of slavery, stereotypes of dark-skinned hypersexuality, and one’s own cultural upbringing can uniquely affect the desires and experiences of non-white leathermen involved in flogging and race-based role play, Mushtaq wrote.

While attending leather events, Mushtaq — who is a dark-skinned Pakistani-American and a former leather title holder — said that other white leathermen have repeatedly told him how “Middle Eastern guys are hot,” or referred to him as “Ali Baba” and “Prince Ali,” two well-known fictional characters from an ancient Arabic folk tale and the 1992 Disney animated film Aladdin, respectively.

Once, at a leather bar in Long Beach, California, a bartender forced a towel over his head and told him that he looked “like a Muslim woman.” When Ali complained to event officials about these degrading experiences, they minimized his concerns and even threatened him, he said.

“This is why we need Onyx,” Mushtaq wrote. “Not only because we have negative experiences in the leather community because we’re men of color; but also, the group provides a space to discuss race in the leather community. Our space is especially helpful when we have a dialogue with our allies who do not identify as a man of color.”

To address these intersections, ONYX has long championed educational workshops and panels on ethnocultural history (like non-traditional family structures in Black communities) or different types of fetish play (like mummification bondage and rope tying). The group holds these informative talks at national conferences like IML, Mid-Atlantic Leather weekend, or local bars and queer community centers.

Though anyone can join ONYX, only men of color can be full voting members; something that occasionally bothers some white leathermen and members with white partners. Mufasa has said that ONYX doesn’t want to discriminate; it just wants to develop leadership and connection among men of color.

Since its founding, the group has accepted trans-masculine, genderfluid, and nonbinary members. It has also always focused on community service. Upon its creation, it began donating to HIV organizations, holding coat drives for trans youth and food drives for local pantries. It has also supported efforts to preserve kink and BDSM history with donations to and presentations at the Leather Archives and Museum in Chicago.

These days, ONYX has about 700 members nationwide and two new chapters developing in Seattle and Arkansas. The national group is currently celebrating its 30th anniversary, with a Blackout 30 Homecoming weekend of fellowship events set to take place in Chicago from October 16 to 19. There, new and old members will connect, dance, dine, go sightseeing, and share their trans-generational experiences.

To Mufasa, now an elder sharing the group’s history with the younger generation, it’s important to keep the organization’s doors open to newcomers rather than just becoming an exclusive “good old boys” network.

“If the brothers did not believe in the vision of community service, of education, and empowerment, then we would have died long ago,” he said. “We’re still growing because there’s still a need. There’s still people finding us.”

Peeker has finally found the social group he’s long been searching for in ONYX. While Peeker’s alias comes partly from his enjoyment of voyeurism (the gaining of sexual pleasure from watching others when they’re naked or engaged in sexual activity), in kink spaces, Peeker didn’t always see other Black men like him. When he shared his kinks with other gay Black men, some would respond negatively, calling him “nasty,” “disgusting,” or a “freak.”

Now, his fellow ONYX brothers have become some of his closest friends. They meet regularly for ONYX meetings on webcam and will carpool and travel together to ONYX and leather events in other states. Outside of ONYX, they’ll meet up at each other’s homes for small get-togethers and barbecues, hang out during evenings in West Hollywood, or just enjoy a meal and share other parts of their lives.

He feels there are probably a lot of other young men who feel like he did earlier in his life: those who feel like they have potential or a life that they can’t quite live out the way they want to, not without some assistance: a little motivation or mentorship.

“It’s really cool to be able to come into a room where we don’t yuck each other’s yums, and I could be authentically myself,” he says. “That really helped me establish these friendships with other people in the same journey. Like, we’re just here to be our authentic selves and show up, have a good time, learn and explore our kinks in an affirming and judgment-free environment.”

“So come meet us,” he says. “We would love to meet each and everybody. We want people to have a good time and be curious. You don’t have to be kinky to hang out. Just come and see what’s up.”

Subscribe to the LGBTQ Nation newsletter and be the first to know about the latest headlines shaping LGBTQ+ communities worldwide.